What is “distressed” debt”?

The most accepted international definition for “distressed debt” is all those bank debts, bonds and obligations issued by companies and governments that are already past due or whose capacity to pay when due is doubtful. However, the Brazilian financial market in general considers debts “distressed” when those corporate obligations of companies are already in either judicial recovery (Brazilian equivalent of US Chapter 11) or bankruptcy procedures or are going into that direction, as perceived by their creditors. Another definition for “distressed” generally includes any debt exposed to the unilateral breaking of contractual obligations by the debtor to the creditor. Yet, another simple and practical definition is to define as “distressed” all debts that are negotiated in the secondary market with a discount to their face value.

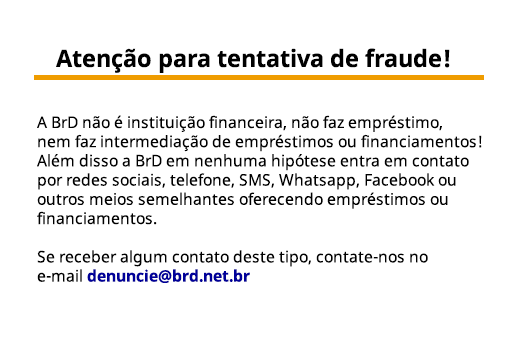

Our Brand

BrD’s brand is a synthesis between elements of the Brazilian flag and the sun’s rays. The highlighted arrow pointed upwards symbolizes our mission to always bring the best results for our clients. BrD’s branding was created and developed by Foresti design.

|

|

Philosophy and valuesOur work philosophy is centered at the rigorous adherence to law, the non-negotiable respect for ethics and the best practice of both Corporate Governance and Compliance. BrD management’s daily decisions are reflected in our slogan, “A win-win Business”, which summarizes what we believe: that BrD can generate advantages for all involved stockholders (stockholders, investors, creditors, debtors, employees and society). The search for excellence in all aspects of our business is the fundamental cornerstone of our core values. We avoid conflict whenever possible, but we are not afraid to litigate in the courts either to defend our interests and principles or to avoid a mediocre consensus which may damage our work philosophy and values.s |

|

For a better world

With small gestures we can contribute to a better society. With this in mind, BrD proudly supports:

BrD Partners

Our partners, apart from developing the philosophy and business strategy, participate in all aspects of BrD’s businesses. They both are seasoned bankers, taking leading positions in renowned financial institutions. They already managed different key areas throughout their careers, such as Trade Finance, Foreign Exchange, Credit (Concession and Recovery) and Risk Management, Corporate Finance, Stock Brokerage and Treasury and Asset and Wealth Management. They also led a series of structured finance deals for Brazilian issuers in both local and international markets.

The team of people that BrD seeks to attract and retain (however employees, consultants or service providers) is composed of individuals who, among others, talents want and necessarily commit to acting:

With optimism and attention to detail

seeing value where others only see problems;

Obsessed with excellence

in the search for results, without ever giving up on our values and principles;Playing as a team

and respecting our “a win win business” philosophy;